Home » Posts tagged 'building class bridges' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: building class bridges

Individualism and Universalism

We Are at Our Best in Community

Unitarian Universalism holds that the individual is the highest authority on their own spiritual health and well-being. No one can tell you what your relationship with the universe should be. We recognize that I cannot fully know and understand what your experiences are or how they have shaped you.

Unitarian Universalism holds that the individual is the highest authority on their own spiritual health and well-being. No one can tell you what your relationship with the universe should be. We recognize that I cannot fully know and understand what your experiences are or how they have shaped you.

But, we must be careful not to fall into the idolatry of the world around us, because the relationship is the thing that we strive for.

Covenantal Faith

Our faith is often called “covenantal.” There is no statement of beliefs that you can recite privately to prove that you are a Unitarian Universalist. You have to make, and keep, a promise to a community.

You have to be a participant in relationships to be fully UU. You have to commit to allowing others to talk to you about your values and ideals and question their place in a responsible life.

You have to accept that you will be encouraged to grow your spirit, even when you are comfortable or growth seems hard. We believe that people are at their best when they are giving their best to the community.

It is easy to fall into the idolization of individuality. We all want to be the hero of our own story, and we want the credit for what we accomplish. But a story is no good without people to listen to it, and no one accomplishes anything in a vacuum. Your community, both in your church and beyond its walls, is at its best when we give everyone the opportunity to be an active participant and give their best back to the community.

Shared Responsibility

To do this, we need to be willing, as a community, to give some support and encouragement to people without them having to earn it on our terms. We need every child to receive a quality education, complete nutrition and adequate shelter. That is how we make them into responsible and compassionate citizens.

We need every person to be guaranteed free time from working to explore the things they love, whether that is painting, music, invention or math. This is how we foster invention and the creation of great art.

We need to address income inequality, as well as the classism behind it, so that those who are struggling can be more fully included in their community, having time and energy to participate. It builds a sense of belonging and shared responsibility.

We need to change how we view the social safety net – not as charity for those who are unable but as support for those who might be able to do more if encouraged and allowed.

We need to put community and a sense of shared responsibility on equal footing with individual achievement and success. Real success should factor in the benefits to the city, the nation and the world. People of every class need to be valued not just for what they have, but how they use it and how much of it they give back.

The United States is in danger of being poisoned by a toxic level of individualism. We’ve lost our civic-minded values, and our infrastructure and education are suffering because of it. We must rekindle the warmth of community if we are ever going to restore the fires of innovation and compassion.

Thomas is the founder and administrator for the I Am UU project. He is passionate about building a better world and a beloved community, and he feels that liberal religion is a vital tool in that construction, and that Unitarian Universalism is the best vehicle for introducing liberal religion to the majority of North America.

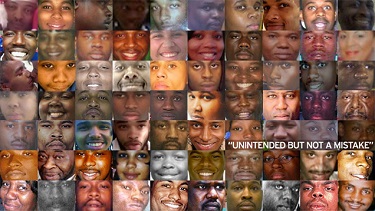

It Will Take Courage to End This Nightmare

by Denise Moorehead

As I listened to the news this week – first about still more unarmed black men dying at the hands of the police and then yesterday morning about 12 Dallas policemen being gunned down – I got angrier and angrier at the hypocrisy of the newscasters and pundits. To avoid being called cop haters or Black Lives Matter apologists, everyone spoke of their shock at what happened in Louisiana and Minnesota and then said, “but how could what happened in Dallas, happen?”

It is ridiculous, even offensive, to pretend that we don’t see the connection between the seemingly unending string of police shootings of black men as well as women and children – some found to be murders – and the very cruel actions of the Dallas shooter. The Dallas shooter left five families without fathers, husbands, sons, brothers, uncles and nephews. I feel truly, truly sorry for their families. It is not fair at all that these officers were randomly chosen to die in this revenge killing.

To refuse to acknowledge the connection, however, is part of the reason that the gunman did what he did. He believed that no one in power is doing anything to stop the random killing of black men across the United States.

To refuse to acknowledge the connection, however, is part of the reason that the gunman did what he did. He believed that no one in power is doing anything to stop the random killing of black men across the United States.

I can never condone what the Dallas shooter did. I have a husband, father and nephew. But I do not pretend that I do not know why he believed his actions were rational. A 2015 study by the Washington Post found that unarmed black men were seven times more likely than whites to die by police gunfire. It is not getting better.

When Class and Race Collide

Police have very stressful jobs and must make life and death decisions in the moment. I’ve been told that when a policeman kills someone in the line of duty, that death stays with him or her forever. But when a string of officers kill 100s of black people each year and virtually none of the police are found guilty of a felony crime, the anger in the black community (and that of our allies) builds and builds – and eventually explodes.

And tinder has been added to the resulting raging fire by further provocations like the recent online sale by George Zimmerman of the gun used to murder Trayvon Martin, the rise of white supremacists (who have openly said Donald Trump’s rhetoric has helped their recruitment), and the continuing demonization of (especially poor and working) black people, especially young black men.

Those of us who care about ending classism and racism see the terrible irony in all of these killings – civilians and police. People from low-income and working-class backgrounds are being pitted against each other.

While black women, men and children of all classes are being harassed, assaulted and killed, a disproportionate number of those killed are less class advantaged. They are mostly low-income or working-class men hustling to make a dollar by selling CDs or cigarettes, driving old cars that have broken down, or in driving “suspiciously” through suburban neighborhoods.

While police in some big cities can make very good incomes, many do not. And most officers have class backgrounds that are not dissimilar from those they must now “police.”

About Class and Race from the Start

It is important to understand the class and race issues underlying the creation of today’s police forces. According to Eastern Kentucky University, the genesis of the modern police organization in the South is the “Slave Patrol,” created to return runaway slaves, deter slave revolts and maintain a discipline among slaves on plantations. Of course, only owning class people had plantations.

While black women, men and children of all classes are being harassed, assaulted and killed, a disproportionate number of those killed are less class advantaged.

In the North, police forces emerged from the hundreds, then thousands of armed men hired by business moguls to impose order on the new working class neighborhoods filling with immigrant wage workers. According to In These Times, Chicago businessmen donated money to buy the police rifles, artillery, Gatling guns, buildings, and money to establish a police pension out of their own pockets.

Speak Up and Show Up

The police were not created to protect and serve all classes. But we must speak up and show support for those police departments that are trying to be a force for all citizens. For example, the Camden, New Jersey, police department was completely revamped in 2013, which has since led to a significant reduction in crime. The department began emphasizing the importance of engaging with the community and forging relationships through one-on-one contact. According to the police chief, the department is focused on “building community first and enforcing the law second.”

Attend your local town meeting, or city council meetings, or aldermans’ meeting when there are police issues, and share the story of Camden and other departments that are trying to serve all classes and races.

And speak up and show up when we see wrong doing. In 2011, the Department of Justice found that the East Haven, Connecticut, police force had engaged in discriminatory policing against Latinos after a local priests’ videotapes helped trigger a federal investigation. Just three years later, federal compliance describe the turnaround within the department as “remarkable.” One person has the potential to make huge change.

Come together with other UUs and other justice-minded people to support:

- our own people of color organizations like Black Lives of UU

- BLM

- the NAACP

- and so many (below)

Refuse to become desensitized to the horror. Don’t change the channel, refuse to listen to the news or simply wring your hands. Talk to your friends and family when they say, “What can we do? It will never change.”

Educate yourself on class and race issues, and on the centuries-old fraught relationship between law enforcement and African-Americans. Refuse to refuse to believe black people when they talk about institutional racism in America.

Write letters to local, state and federal officials. Tell the Obama Administration and (especially) Congress that in a federal budget of $56 billion for police grants, it is a tragedy that only $70 million is allocated to improve police-community relations. (And much of that $70 million is for body-worn cameras, not community engagement.)

See the long list below of actions you can take and groups you can join and/or support.

And vote for people who can bring us together, not tear us further apart.

We know what it will take to end this nightmare. Now let’s summon the courage to do so.

More Reading/Listening

- We Already Know How to Reduce Police Racism and Violence

- This Country Needs a Truth and Reconciliation Process on Violence Against African Americans—Right Now

- Class and The Movement for Black Lives

- Can faith communities heal racial inequality? In Kansas City, a resounding yes

Organizations

- Black Lives Matter

- Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence

- Campaign Zero – Solutions

- Color of Change’s petition calling for justice for Alton Sterling and Philando Castile

- Cut50.org (founded by Van Jones)

- NAACP

- Newtown Action Alliance

- Showing Up for Racial Justice (link to Black-led racial justice organizations you can support)

- The ACLU Mobile Justice App

Don’t Feed the Birds, Animals — or People?

When I learned about the latest indignity aimed at people living in persistent poverty, I had to ask myself, How did we dehumanize people living in poverty so thoroughly?

According to the National Coalition for the Homeless, well over 30 municipalities have restricted or banned sharing food with homeless people across the USA. Learning about this horror made me think about how (increasingly) rare it is for people from different class groups – and even with different class backgrounds – to interact. It becomes easy to view someone as “the other” when you see them only from afar – if you see them at all.

This thought brought back memories of one summer, during the mid-80s, when I saw how the myth of “other” began to crumble ever so slightly for one young man.

Creating Change

I worked on a grassroots campaign to pass a Consumer Utility Bill (CUB), which would have allowed consumers to contribute $1 to hire an expert to rebut Utility Company testimony during rate hike hearings. No one had organized Chelsea, home of the House Ways and Means Committee Chairman, Richie Voke. Ever.

Chelsea was the poorest city in Greater Boston, and one of the poorest in the state. It was expected that my crew would last a couple of hours, at most. But with youthful optimism and energy, I gathered all the multilingual canvassers who would accept my invitation, and off we went. Our assignment was to gather handwritten letters to deliver to Rep. Voke, as well as contributions of any amount (wink, wink).

As that one evening stretched into the second week, a young man in preppie attire balked at joining the crew. “Of course, it is easy for you. You’re working class.” Ummm.

Not exactly. I explained that I had grown up in a well-to-do suburb of Boston. Once upon a time, it was known as “one of the three Ws for wealth: Winchester, Weston, and Wellesley.” Moreover, I had graduated with honors from Harvard-Radcliffe College just a few years before, albeit on scholarship.

Well, perhaps he could give it a try, even though he was coming from an upper class family on the North Shore. He grudgingly came with us to Chelsea.

Opening a Window

Given his misgivings, we agreed to a check-in within the first hour. Turning the corner toward the designated meeting spot, I wondered what I would find. Up ahead, the young man stood quietly, as if trying to avoid attention. As he slid into the passenger seat, he was beaming. He waved a letter in his hand, and exclaimed, “You were right, Nancy. Working class people are just like us!” I did bite my tongue. His sincere amazement caught my breath.

This young man joined us for a second evening, and his enthusiasm contributed greatly to our campaign. All told, we visited Chelsea for two weeks, gathered 50 letters, over 250 signatures, and many memberships. It turns out that Chelsea is a city with many different neighborhoods, and socioeconomic classes. We even received a $50 contribution (well before the gentrification and condos of the new millennium).

Richie Voke responded immediately, rescuing the CUB and setting it up for passage. Unfortunately, in October that year, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a similar provision, disallowing consumers to piggy-back communication in the utility statement envelopes. Alas. The campaign was successful in so many ways, for all of us.

Widening the Circle

Perhaps my own openness to all classes developed from the economic reality of my childhood in Winchester. Recently, my mother informed me that we would have had more money if she, as a widow with two small children, had applied for welfare. Instead, my grandparents assisted with budgeting (not actual funds) and my experience of socioeconomic realities was fluid and not particularly painful. I worked from the age of nine, but then so did many babysitters.

Whatever our response to the challenges of class discrimination, we cannot leave our cross-cultural encounters to chance. Class conversations are one way to begin deliberate steps toward widening our Circle of We, and ending classism.