Blog Post: We the People

“There is no history without African-American history …”

Sarah Clarke Kaplan, the executive director of the Antiracist Research and Policy Center at American University sums up a salient point in the celebration of Black History month. The ongoing perception of some Americans that certain Americans are more American than others and that the stain of slavery is only the shame of those of African decent, perpetuates the ignorance that is still shaping the laws of our country.

As the politicized debate rages on about whether or not there is value in teaching students all of our history, we as Americans can embrace the idea that the history of any racial or ethnic group should not be relegated to 3 or 4 weeks each year. It is incumbent on all of us to introduce ourselves and our youth to the diversity in American literature, art, music and widen our own definitions of what is Americana.

Due to COVID restrictions, most museums offer virtual tours. Why not visit the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture here or review some art at the Smithsonian Museum of African Art here, or research what is available in your local town or city? Become an active participant in learning about what makes our country so unique, and celebrate it by submerging yourself in all the differences that make this country a true melting pot of cultures. If not for us, the average citizens, and our storytelling traditions, much of our rich and diverse history could have already been lost.

History has a way of repeating itself, and if we the people allow alternative facts to reshape the history of our country, we will allow our history to be whitewashed and erased. It has happened before; the quaint pictures of Native people sharing a feast with Pilgrims and the smiling faces of slaves singing spirituals while picking cotton would be laughable if not for their blatantly shameful attempt at historical propaganda.

The importance of preserving and celebrating our ethic and cultural uniqueness and value is tantamount to protecting the social justice and rights of all Americans and our civil liberties.

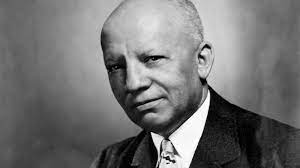

Dr. Carter Woodson, a noted historian, author and journalist and the founder the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, advocated for the national acknowledgment and celebration of the contributions American Blacks made to American history. He launched Negro History Week in 1926.

Dr. Carter Woodson, a noted historian, author and journalist and the founder the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, advocated for the national acknowledgment and celebration of the contributions American Blacks made to American history. He launched Negro History Week in 1926.

He chose the second week in February, since it commemorates both Abraham Lincoln’s and Fredrick Douglas’ birthdays, two men integral in the emancipation of African Americans.

The 2022 Theme of Black History month has been Black Heath and Wellness.

Fifty years after the inaugural event, President Ford officially recognized the week in 1976. It became a nationally celebrated month in 1986, coinciding with the recognition of Martin Luther King Day in January. Learn more about Dr. Woodson and the continued work of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

My story of wage differentials in a small factory

David H. Slavin

David H. Slavin

In the early 1970s, I helped found the “NY Collective,” a group of ex-SDS student radicals who had transitioned to workplace organizing. It later became Harper’s Ferry Organization and counted Theodore William Allen [author of the 2 vol. history _The Invention of the White Race_] among its founding members. Between jobs in the Post Office and the NY Transit Authority, I sought work in one of what at the time were hundreds of small factories in Long Island City (Queens). Noticing a ‘help wanted’ sign at one factory door, I walked in–off the street and filled out a short application. The foreman hired me on the spot. The shop handmade high-end, polished wood restaurant bars along with sinks and other stainless steel commercial kitchen equipment. I thought it would be great opportunity to learn a skilled trade in wood working. After filing my paperwork, the foreman took me aside and said, “Listen. I’m going to start you at $1.75 an hour, but keep it under your hat because other guys’ starting salaries are less.” He took me from the office to the shop. To my disappointment we passed through the woodworking section, where the workers were mostly middle-aged white men, and on to the steel sink manufacturing area in the back, where the workers were mostly young Hispanics. The foreman left me with the Hispanic lead worker. My first job was using a nail gun to knock together wooden shipping crates to protect finished sinks while they were being transported.

I can’t crawl inside the foreman’s head, but clearly he had decided to pay me more because he perceived me to be white and decided that I would need the incentive of a “white wage” to stick with the job. Other factors, such as English fluency and my claim to high school education (unverified except by the fact that I filled out the application form quickly and without errors), likely influenced his decision. Even those factors were part of my “white package,” so, realistically, his preferential treatment of me came down to race. So I faced the classic dilemma of solidarity or favoritism from the moment I walked in the door of the plant.

At this point in the story I might ask readers, what would be my next step, or flippantly (but respectfully) “what would Jesus do?” Unskilled or semi-skilled factory work may be more rare today than forty years ago, but as union contracts are torn up, union strength erodes, management imposes two-tier wages and benefit plans, labor laws are ever more laxly enforced, and as production in many IT-based sectors increasingly isolates workers, employers have been able to eliminate statutory starting pay and raises based on seniority, inflation and other objective criteria. Bargaining for wages has become less collective than at any time since the 1930s. Bosses and free market economists love to present such negotiations as two equal parties making a contract, an illusion that masks the realities of asymmetrical power — of who owns the means of production as private property protected by the full power of the state — and who has the ability to pit groups of workers against each other in a drive to the bottom, locally or globally and everywhere in between.

Before I divulge my course of action, I want to mention several solutions suggested by two longtime activists who attended a talk I gave in 2007 at the US Social Forum in Atlanta: one a community organizer and the other a union organizer. The former advised that I go back to the foreman and argue with him that paying me more was unfair to the other workers. I pointed out that in the context of class struggle, saying anything to any foreman except in the company of the rest of the workers in the shop, or through a union rep, was foolish and losing proposition. Going up against him alone identified me as a troublemaker who could be isolated if not fired. Individualism makes every working person vulnerable, and it ignores the main strength of workers–solidarity, their ability to band together and defend each other as part of the working class.

The union organizer, years my senior and with decades of experienced, counseled proceeding with caution. Spend a few weeks gaining the trust of the other workers, doing my job, eating lunch with them, etc., he said. Then tell them about the wage differential. In other words, he advised lying by omission until I gained their “trust” only to reveal how I had betrayed it. Moreover, this “organizer” was unable to see or understand what the 15 cents an hour was doing to _me_ as the recipient of this largesse. The secret deal put me under tacit obligation to, and in collusion with, the foreman. It made me beholden to him and isolated me from my fellow workers. The 10% differential acted like a poison pill, creating dependency on the boss. It neutralized and neutered me as a worker. To understand that lesson — solidarity first, last and always — “organizers” need to spend their time on the shop floor listening to their comrades, building awareness of power inequalities, and raising their own class consciousness before advocating a course of action.

I took the following steps: After spending the morning under the direction of the lead man in the metal shop, who spoke English, taught me the job and watched me carrying out the tasks until he was satisfied I could do them safely (his number one priority) on my own. At the first chance I could, the morning coffee break, I told him that the foreman had hired me at $1.75 an hour. His face went dark, and he immediately told the others in Spanish. He then pointed out two or three young men and said “these guys have been working here for 18 months and are still making $1.60.” Out of the dozen or so in the shop, everyone was upset or angry, directing not a little hostility at me.

My Spanish was passable at the time; I thought I could make myself understood. So I said in a firm voice, “Estoy listo de ir a la huelga para todos los companeros muchachos ganar $1.75.” I’m ready to go on strike for all the comrades – guys to get $1.75 an hour.

The barometric pressure in the room changed, and the impending storm shifted course from the “white boy” to the foreman. They huddled, speaking too rapidly for me to understand. I think they were discussing a walkout. There was no strike, but some time that afternoon the lead man and several others went to the foreman and gave him a piece of their collective mind. As for me, I was accepted, more fully by some, including the lead man, more grudgingly by others. But I was a part of the shop, not a tool of the boss. Over the next days, they told me stories.

All were Dominicans, many coming up to the US after LBJ sent in the marines in 1965 to overthrow Juan Bosch and the leftist, democratically elected regime he led. Many had been “communists,” i.e. union workers in the Dominican Republic. The union in this shop, the Carpenters Union, was one of the most corrupt in NYC. The only grievances it ever processed were those of the white cabinet makers in the front room. The only time my guys ever saw a union business agent was to inform them of dues increases. The powerlessness of the union was clear to me. In a shop with a union with real teeth, a foreman wouldn’t dare to take it on himself to pay more — or less — than the union scale.

One last point: at the end of the day the foreman angrily took me aside and said something to the effect that “I told you to keep your mouth shut. You made a lot of trouble for me today.” I decided the best defense was to play “dumb worker” and mumbled something about, gee it must have just slipped out. Punching out, I went chuckling on my way home. A few days later, I recounted the story to a meeting of Harper’s Ferry, and I never saw Ted Allen looking so pleased. I had slain the Jabberwock, white privilege. He positively chortled.

“And, has thou slain the Jabberwock?/ Come to my arms, my beamish boy! / O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay! / He chortled in his joy.

JABBERWOCKY Lewis Carroll (from Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, 1872)

Living Wage

By Micheal Greenwood

There is a lot of talk in Washington D.C. and elsewhere these days about increasing the Federal minimal wage to $15.00 from $7.25 which was set in 2009. Today, inflation has made that 2009 dollar worth 72 cents.

Many states have already increased their minimum hourly wage. Is your state one of them?

To learn if it is follow this link, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/minimum-wage or https://www.epi.org/publication/labor-day-2019-minimum-wage

Even if your state does exceed the current minimum hourly wage of $7.25 an hour, is it enough to meet the cost of living where you reside? To learn if it is, follow this link https://livingwage.mit.edu So when we talk about an hourly wage of $15.00 remember it still is not a living wage for most folks in the United Sates.

Stop the Hate Against AAPI Communities

Systemic racism and acts of terror towards Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have dominated media headlines in the past few months. Sadly, while hate incidents against the AAPI community have escalated in the past year, surpassing 6,000 reported incidents between 2020 and 2021, this not a recent occurrence in America.

Systemic racism and acts of terror towards Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have dominated media headlines in the past few months. Sadly, while hate incidents against the AAPI community have escalated in the past year, surpassing 6,000 reported incidents between 2020 and 2021, this not a recent occurrence in America.

Anti-Asian sentiments, oppression and violence date back centuries.

The United States imported Chinese workers in the 19th Century to build the railroad system. Once it was built, the workers, who had been cheap sources of labor for employers, were seen as competition by many White working class Americans. The anti-Asian sentiments led to Chinese men and their families being driven from towns, lynched and subjected to newly passed anti-immigration laws.

We have witnessed anti-Asian sentiments becoming increasingly hostile during the pandemic, escalating from verbal to physical attacks to most recently, mass murder.

The belief that Asians carry disease and that they should return to Asia no matter how many generations their family has been in America is often shared on social media. Many Americans also confuse the concepts of country and continent and label Asians as a single demographic, all from the same place. This diminishes the rich and varied cultural beliefs, values, religions and spiritual traditions of the Asian diaspora.

Rich Culture(s)

There are many ethnic identities, cultures and languages within this diverse group of people. In the United States alone, this racial category, according to the Census, refers to more than 40 different ethnic groups. Moreover, in the past 40 years, there has been a widening of income inequality among Asian populations, which has led to social and economic consequences for some. Education and income levels vary widely among Asians. Although they rank as the highest earning racial and ethnic group in the United States, the wide and rapid economic divide belies the growing class differences within this group.*

One lingering remnant from the immigration laws restricting Asian migration within the United states is that a large percentage of Asians and Asian Americans still live in states where there were major points of entry for earlier Asian immigrants, such as New York, California and Hawaii.

While Asian migration throughout the United States has been more prevalent since the mid-1960s, when these laws were overturned, there are still places in the United States where Asians are viewed as exotic and foreign, and not “real” Americans. It is not incidental that people of Japanese descent in America, not German, were imprisoned in internment camps during World War II.

Next Steps for UUs?

What does this mean for us as UUs? We at UU Class Conversations believe that remaining true to our Principles will help break down divisions along class and racial lines. Creating an inclusive community for all racial and ethnic groups begins with meaningful and productive dialogue aimed at combatting racial and class injustice.

What do you see then as next steps for this work?