It Will Take Courage to End This Nightmare

by Denise Moorehead

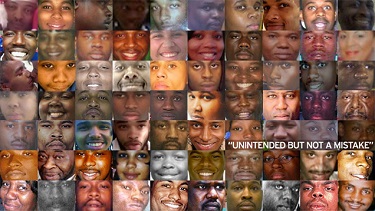

As I listened to the news this week – first about still more unarmed black men dying at the hands of the police and then yesterday morning about 12 Dallas policemen being gunned down – I got angrier and angrier at the hypocrisy of the newscasters and pundits. To avoid being called cop haters or Black Lives Matter apologists, everyone spoke of their shock at what happened in Louisiana and Minnesota and then said, “but how could what happened in Dallas, happen?”

It is ridiculous, even offensive, to pretend that we don’t see the connection between the seemingly unending string of police shootings of black men as well as women and children – some found to be murders – and the very cruel actions of the Dallas shooter. The Dallas shooter left five families without fathers, husbands, sons, brothers, uncles and nephews. I feel truly, truly sorry for their families. It is not fair at all that these officers were randomly chosen to die in this revenge killing.

To refuse to acknowledge the connection, however, is part of the reason that the gunman did what he did. He believed that no one in power is doing anything to stop the random killing of black men across the United States.

To refuse to acknowledge the connection, however, is part of the reason that the gunman did what he did. He believed that no one in power is doing anything to stop the random killing of black men across the United States.

I can never condone what the Dallas shooter did. I have a husband, father and nephew. But I do not pretend that I do not know why he believed his actions were rational. A 2015 study by the Washington Post found that unarmed black men were seven times more likely than whites to die by police gunfire. It is not getting better.

When Class and Race Collide

Police have very stressful jobs and must make life and death decisions in the moment. I’ve been told that when a policeman kills someone in the line of duty, that death stays with him or her forever. But when a string of officers kill 100s of black people each year and virtually none of the police are found guilty of a felony crime, the anger in the black community (and that of our allies) builds and builds – and eventually explodes.

And tinder has been added to the resulting raging fire by further provocations like the recent online sale by George Zimmerman of the gun used to murder Trayvon Martin, the rise of white supremacists (who have openly said Donald Trump’s rhetoric has helped their recruitment), and the continuing demonization of (especially poor and working) black people, especially young black men.

Those of us who care about ending classism and racism see the terrible irony in all of these killings – civilians and police. People from low-income and working-class backgrounds are being pitted against each other.

While black women, men and children of all classes are being harassed, assaulted and killed, a disproportionate number of those killed are less class advantaged. They are mostly low-income or working-class men hustling to make a dollar by selling CDs or cigarettes, driving old cars that have broken down, or in driving “suspiciously” through suburban neighborhoods.

While police in some big cities can make very good incomes, many do not. And most officers have class backgrounds that are not dissimilar from those they must now “police.”

About Class and Race from the Start

It is important to understand the class and race issues underlying the creation of today’s police forces. According to Eastern Kentucky University, the genesis of the modern police organization in the South is the “Slave Patrol,” created to return runaway slaves, deter slave revolts and maintain a discipline among slaves on plantations. Of course, only owning class people had plantations.

While black women, men and children of all classes are being harassed, assaulted and killed, a disproportionate number of those killed are less class advantaged.

In the North, police forces emerged from the hundreds, then thousands of armed men hired by business moguls to impose order on the new working class neighborhoods filling with immigrant wage workers. According to In These Times, Chicago businessmen donated money to buy the police rifles, artillery, Gatling guns, buildings, and money to establish a police pension out of their own pockets.

Speak Up and Show Up

The police were not created to protect and serve all classes. But we must speak up and show support for those police departments that are trying to be a force for all citizens. For example, the Camden, New Jersey, police department was completely revamped in 2013, which has since led to a significant reduction in crime. The department began emphasizing the importance of engaging with the community and forging relationships through one-on-one contact. According to the police chief, the department is focused on “building community first and enforcing the law second.”

Attend your local town meeting, or city council meetings, or aldermans’ meeting when there are police issues, and share the story of Camden and other departments that are trying to serve all classes and races.

And speak up and show up when we see wrong doing. In 2011, the Department of Justice found that the East Haven, Connecticut, police force had engaged in discriminatory policing against Latinos after a local priests’ videotapes helped trigger a federal investigation. Just three years later, federal compliance describe the turnaround within the department as “remarkable.” One person has the potential to make huge change.

Come together with other UUs and other justice-minded people to support:

- our own people of color organizations like Black Lives of UU

- BLM

- the NAACP

- and so many (below)

Refuse to become desensitized to the horror. Don’t change the channel, refuse to listen to the news or simply wring your hands. Talk to your friends and family when they say, “What can we do? It will never change.”

Educate yourself on class and race issues, and on the centuries-old fraught relationship between law enforcement and African-Americans. Refuse to refuse to believe black people when they talk about institutional racism in America.

Write letters to local, state and federal officials. Tell the Obama Administration and (especially) Congress that in a federal budget of $56 billion for police grants, it is a tragedy that only $70 million is allocated to improve police-community relations. (And much of that $70 million is for body-worn cameras, not community engagement.)

See the long list below of actions you can take and groups you can join and/or support.

And vote for people who can bring us together, not tear us further apart.

We know what it will take to end this nightmare. Now let’s summon the courage to do so.

More Reading/Listening

- We Already Know How to Reduce Police Racism and Violence

- This Country Needs a Truth and Reconciliation Process on Violence Against African Americans—Right Now

- Class and The Movement for Black Lives

- Can faith communities heal racial inequality? In Kansas City, a resounding yes

Organizations

- Black Lives Matter

- Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence

- Campaign Zero – Solutions

- Color of Change’s petition calling for justice for Alton Sterling and Philando Castile

- Cut50.org (founded by Van Jones)

- NAACP

- Newtown Action Alliance

- Showing Up for Racial Justice (link to Black-led racial justice organizations you can support)

- The ACLU Mobile Justice App

Lifting Water Communion above Privilege and Trivia

By Rev. Amy Zucker Morgenstern

By Rev. Amy Zucker Morgenstern

A Unitarian Universalist friend and I were talking about class tensions in church, and he said that he found Water Communion hard to bear because it was so much about the places people had gone on their summer vacations.

Oh yeah. I’ve been to some Water Communions that felt that way too. It is so easy for our ingathering ceremony, in which people bring water and pour it into a communal bowl, to turn into a “what I did on my summer vacation” recitation, which can make the ritual obliviously exclusive of those who don’t have summer homes, or summer vacations, or the money for airfare, or the luxury to stop working for even one week out of the year. What a shame; it’s so opposite of what the Water Communion can be.

The core symbolism of the Water Communion is that we all come from water: as a species on a planet where life began in the ocean, as mammals who float in amniotic fluid as we are readied for birth, as beings whose cells are mostly water. And yet we are separate from each other, and we have been apart–since there tends to be a slowing-down, a different rhythm in the summer months, even in churches that have services and religious education right on through the summer – and now we are reuniting. We are separate and together, the way water scatters into rain and streams and clouds and springs and ponds and puddles and yet flows together again and again, one great planetary ocean. Not only is no drop of water superior to any other; all water comes from the same place.

So the class issue is only a part of what’s awry with the “where I went this summer” approach to the ritual. Even if everyone in the world had a summer home in Provence, “This water comes from our summer home in Provence” would not be what I wanted this ceremony to be about. It’s so trivial, whereas “We are separate beings and yet all one” is one of the profoundest truths we try to encompass.

I’ve deliberately shaped our Water Communion at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto (UUCPA) with these concerns in mind, and that conversation with my friend made me realize that other UUs could learn from that process, so I’m going to share it here. I’d also like to learn from readers: judging by this description, or by your experience of UUCPA’s Water Communion if you’ve been there, have we succeeded? And what do you do in your congregation to keep our attention focused on the deepest meanings of the Water Communion?

Here are some dos and don’ts that have guided me.

Don’t: have an open mike where everyone describes where the water came from. Not only is this impractical for any but the smallest congregations, but it just about orders people to say “We brought this from the Mediterranean, where we went on a beautiful cruise.”

Do: provide a way for people to share the significance of the water they’ve brought, and have a leader or leaders share a precis. Doing this has allowed me to rephrase people’s descriptions in a way that honors the most important aspects, while playing down the others. So, for example, if someone writes, “This water comes from our family’s summer home on Cape Cod, where I’ve gone since I was a small child visiting my grandparents–this year I was there with my grandchildren,” I might share, “Water from the Atlantic Ocean,” or “Water from a place made sacred by five generations of one family,” or “Water from a multigenerational family gathering,” or some combination of those.

Do: frequently model modest origins for your own water. I usually bring mine from my home tap, even if I’ve been somewhere exotic. (In the spirit of full disclosure, one reason is that when I do travel, I always forget to bring back a little bottleful . . . !)

Do: make reference to the water’s many sources. At UUCPA, we have banners that artistically express the four directions and elements; sometimes we use those in this service and people pour their water into a bowl under one of the banners. They can have a time of meditation to think about where their water comes from, symbolically or literally, and choose the direction/element accordingly. Jane Altman Page wrote nice words to accompany something like that here, on the Worship Web.

Don’t: just pour the water down the drain. While keeping it in the water cycle, that doesn’t honor the sacredness of the ritual. People are bringing something of themselves when they bring that “water from a special day at the beach” or “tap water from my great-grandfather’s house,” so it’s important to let them know that it will be treated with due reverence.

Do: do something important with the water. For example, carry it out ceremoniously after the service and water a special tree. . . . Bless it and invite everyone to put it on their foreheads / hands / feet / hearts. . . . We save some of ours for dedications throughout the year, and pour some in from last year’s dedication water so that the water is now gathered from many years of rituals (does anyone else do this? I don’t even remember if I came up with that idea, or inherited it on arriving in Palo Alto). I usually pour the rest out on our grounds with some words of thanks and praise. (A comment by a church member just reminded me of another possibility: invite people to bring some of the mingled water home, the way we do with the flowers at Flower Sunday, and encourage them to mindfully use it, e.g., to water a plant.)

Do: frame the ritual in terms of its larger meanings. There are so many. Our Minister of Religious Education, Dan Harper, has done a wonderful, geeky demonstration of just how many molecules of water we’re talking about, and how big a number that is. (Remember, we’re serving in Silicon Valley. When you ask, “Are there any geeks here who can come hold this paper for me?,” many hands shoot up.) He uses that to prove our literal interdependence. The year Water Communion was preceded by Hurricane Katrina, we had to talk about the destructive power of water, and that was a chance to go into some theological depth.

And, if you’re reminding folks about Water Communion now, as summer starts,don’t emphasize that they should bring their water back from special travels. There’s no need to mention travel at all. This year, my reminder in the newsletter said “We bring water from the places of our lives.”

I’d love to hear what others do.

Rev. Amy Zucker Morgenstern is the minister at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto and author of the blog Sermon in Stones, which she began in 2010. In her posts, she explores matters of religion (theology, ecclesiology, congregational dynamics, you name it), art, literature, politics, philosophy, and culture.

I Work, Therefore I Am …

by Bethany Ramirez

by Bethany Ramirez

UU Class Conversations

Advisory Board member

Defining Working Class

How do you define “working class”?

The girlfriend of a friend of mine used to insist that she was working class because her parents worked. They paid for her car, utilities and all of her credit card bills. They paid all of her undergraduate tuition without financial aid. They even paid for the weekly maid service she enjoyed.

She used to casually stop into Nordstrom’s (an upscale department store) and drop $200 on a single pair of shoes on a whim, because her parents would pay the bill. The only thing she paid for was her half of the rent on a 4-bedroom waterfront condo for just the two of them – which she could not have afforded if her parents hadn’t been paying for everything else.

She used to casually stop into Nordstrom’s (an upscale department store) and drop $200 on a single pair of shoes on a whim, because her parents would pay the bill. The only thing she paid for was her half of the rent on a 4-bedroom waterfront condo for just the two of them – which she could not have afforded if her parents hadn’t been paying for everything else.

She used to chide my friend for being broke all the time even though he technically made more than she did (by only a few thousand). He had student loans. He had to pay all of his bills himself. He owed money on his car. He did not have parents who could underwrite spontaneous $200 purchases of shoes.

She genuinely could not understand why he was financially strapped all of the time.

Understanding Class Privilege

And this, to me, is why I have never been able to view her as working class. Well into her 30s her parents supported her in a life of comfort. And she so firmly believed that she was working class (because she and her parents worked) that she could not understand that it wasn’t the same for everyone else.

By the classic definition “nothing to sell but labor-power and skills,” she was working class. But when it comes to privilege and relating to money, it always felt like she came from a different world. She chose to work. But her parents had enough wealth that she didn’t have to. And she had no concept of what it was like to have to rely on income from a job in order to survive.

This makes me feel that the definition was too broad. She can define herself as working class, and a dictionary can define her as working class, but I cannot accept that she is working class.

Leave comment, and let me know: Where is the line for you?

Don’t Feed the Birds, Animals — or People?

When I learned about the latest indignity aimed at people living in persistent poverty, I had to ask myself, How did we dehumanize people living in poverty so thoroughly?

According to the National Coalition for the Homeless, well over 30 municipalities have restricted or banned sharing food with homeless people across the USA. Learning about this horror made me think about how (increasingly) rare it is for people from different class groups – and even with different class backgrounds – to interact. It becomes easy to view someone as “the other” when you see them only from afar – if you see them at all.

This thought brought back memories of one summer, during the mid-80s, when I saw how the myth of “other” began to crumble ever so slightly for one young man.

Creating Change

I worked on a grassroots campaign to pass a Consumer Utility Bill (CUB), which would have allowed consumers to contribute $1 to hire an expert to rebut Utility Company testimony during rate hike hearings. No one had organized Chelsea, home of the House Ways and Means Committee Chairman, Richie Voke. Ever.

Chelsea was the poorest city in Greater Boston, and one of the poorest in the state. It was expected that my crew would last a couple of hours, at most. But with youthful optimism and energy, I gathered all the multilingual canvassers who would accept my invitation, and off we went. Our assignment was to gather handwritten letters to deliver to Rep. Voke, as well as contributions of any amount (wink, wink).

As that one evening stretched into the second week, a young man in preppie attire balked at joining the crew. “Of course, it is easy for you. You’re working class.” Ummm.

Not exactly. I explained that I had grown up in a well-to-do suburb of Boston. Once upon a time, it was known as “one of the three Ws for wealth: Winchester, Weston, and Wellesley.” Moreover, I had graduated with honors from Harvard-Radcliffe College just a few years before, albeit on scholarship.

Well, perhaps he could give it a try, even though he was coming from an upper class family on the North Shore. He grudgingly came with us to Chelsea.

Opening a Window

Given his misgivings, we agreed to a check-in within the first hour. Turning the corner toward the designated meeting spot, I wondered what I would find. Up ahead, the young man stood quietly, as if trying to avoid attention. As he slid into the passenger seat, he was beaming. He waved a letter in his hand, and exclaimed, “You were right, Nancy. Working class people are just like us!” I did bite my tongue. His sincere amazement caught my breath.

This young man joined us for a second evening, and his enthusiasm contributed greatly to our campaign. All told, we visited Chelsea for two weeks, gathered 50 letters, over 250 signatures, and many memberships. It turns out that Chelsea is a city with many different neighborhoods, and socioeconomic classes. We even received a $50 contribution (well before the gentrification and condos of the new millennium).

Richie Voke responded immediately, rescuing the CUB and setting it up for passage. Unfortunately, in October that year, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a similar provision, disallowing consumers to piggy-back communication in the utility statement envelopes. Alas. The campaign was successful in so many ways, for all of us.

Widening the Circle

Perhaps my own openness to all classes developed from the economic reality of my childhood in Winchester. Recently, my mother informed me that we would have had more money if she, as a widow with two small children, had applied for welfare. Instead, my grandparents assisted with budgeting (not actual funds) and my experience of socioeconomic realities was fluid and not particularly painful. I worked from the age of nine, but then so did many babysitters.

Whatever our response to the challenges of class discrimination, we cannot leave our cross-cultural encounters to chance. Class conversations are one way to begin deliberate steps toward widening our Circle of We, and ending classism.